The cycle that can’t be recycled

26 November 2025

In 2019, bitcoin analyst PlanB introduced the stock-to-flow model. With this model, he made price predictions based on bitcoin’s so-called four-year cycle. Every four years—or more precisely, every 210,000 blocks—the inflation rate of bitcoin halves during the bitcoin halving. According to the model, this reduction increases scarcity, resulting in higher prices.

It’s an interesting theory, yet today’s new generation of bitcoin investors is increasingly unaware of its existence. Meanwhile, one of the foundations of the model is more relevant than ever…

Moving the goalposts

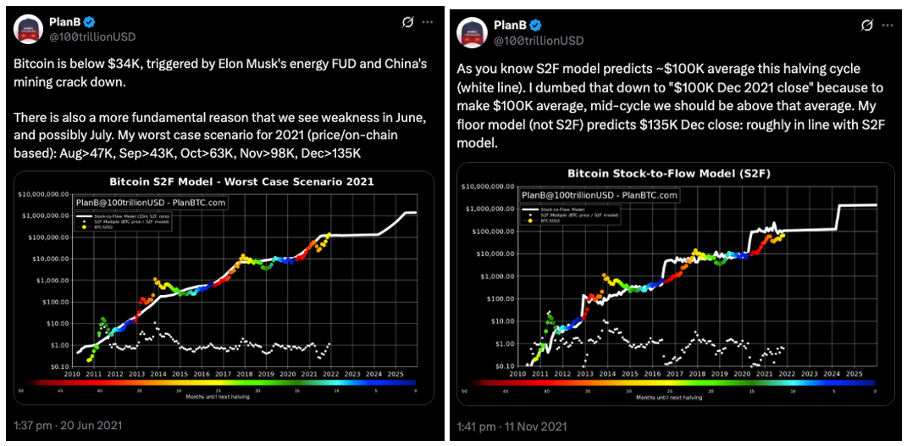

According to the (then current) stock-to-flow model, one bitcoin was expected to be worth around $100,000 in 2021. When that prediction didn’t materialize, the interpretation shifted to an average price of $100,000 between 2020 and 2024. And when that expectation also proved incorrect, the narrative shifted back to the original model—simply because it came closest.

https://x.com/100trillionUSD/status/1406577006230245376

https://x.com/100trillionUSD/status/1458776821932048387

https://x.com/100trillionUSD/status/1821902625832382625

These shifting goalposts were confusing, but also revealing. As the four-year cycle predicted, bitcoin did reach new highs at the end of 2020 and again four years later in 2024. But the way it happened and the nature of those price movements were far more unpredictable. And when the phases of a cycle increasingly diverge from one another, can we still call it a cycle?

Not a four-year cycle, but a multi-year pattern

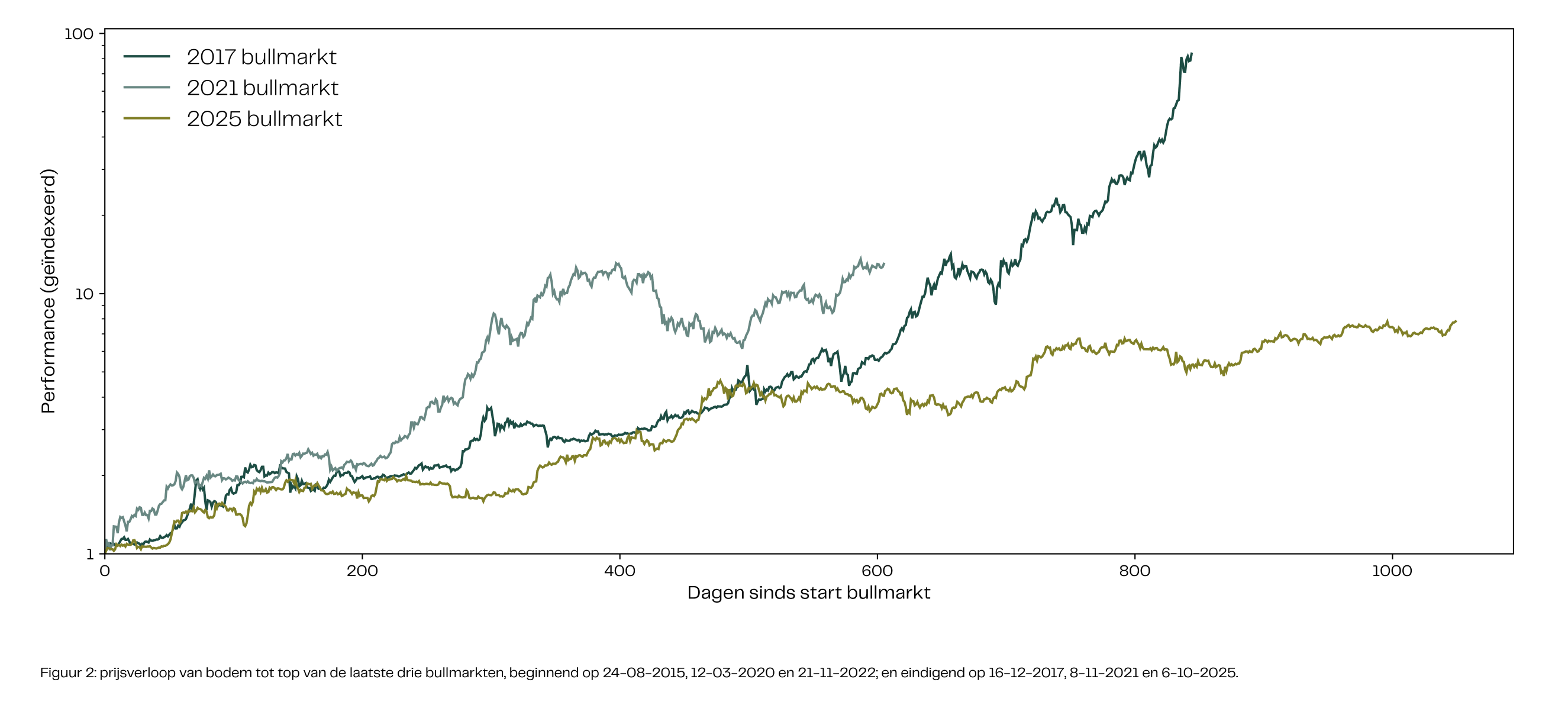

Bitcoin is now in a bull market that has been ongoing since late 2022. That is longer than any bull market we’ve seen before. Moreover, the current bull market isn’t increasing in intensity—something clearly observable in 2017 and 2021. And volatility, instead of rising, has been decreasing.

Everything suggests that this cycle is not characterized by euphoria, greed, or FOMO. Bitcoin is gradually appreciating, and reckless speculation in risky altcoins is largely absent. In short: no repetition of previous cycles, no predictable rhythm—just an upward price pattern that seems to emerge every few years.

A grand prophecy

One common explanation for the four-year cycle is market inefficiency. The idea is that although the timing of the halving is public knowledge, the market is too inefficient to price it in correctly.

What is often overlooked, however, is that it’s not investors but bitcoin miners who are directly affected by the halving. Their revenue is cut in half overnight. And since many miners are publicly listed companies, it seems highly unlikely that they would be caught off guard without a strategy to absorb this shock. In other words: inefficiency is already removed at the miner level—long before the broader market reacts.

In my view, the psychology of self-fulfilling prophecies is the strongest argument in favor of the four-year cycle. The market believes the cycle exists, acts accordingly, and thereby creates the very pattern it expects. But as investors struggle to find similarities with previous cycles, this perception will inevitably fade—and the pattern will eventually dissolve.

He who pays, decides

One of the central trends of recent years is the widespread adoption of digital assets across different domains. The launch of bitcoin ETFs has made access to the crypto market easier than ever. Public companies, pension funds, and even several countries now hold bitcoin on their balance sheets, and crypto is increasingly viewed as part of a diversified multi-asset portfolio.

The result is that the crypto market is no longer seen as an isolated high-risk investment, but as part of a larger financial ecosystem. Given today’s correlation and interconnectedness with traditional markets, the question arises: does bitcoin still move according to a four-year cycle? Large asset managers are now the ones allocating capital— and those who pay, decide.

Leading by example

The four-year cycle is a phenomenon whose characteristics are fading, for which no durable underlying causes can be identified, and which is losing relevance due to recent market developments. It’s not so much that the cycle has died—it has simply been overtaken by reality. And the likelihood that this perceived law of nature will soon disappear is greater than ever, much like the stock-to-flow model before it.

Tim is a Quantitative Portfolio Manager. He holds an MSc in Econometrics and leads the quantitative team. Tim is mainly responsible for quantitative research and development.

Our website uses cookies

We use cookies to personalize content and advertisements, to offer social media features and to analyze our website’s traffic. We’ll also share information about your usage with our partners for social media, advertising and analysis. These partners can combine this data with data you’ve already provided to them, or that they’ve collected based on your use of their services.